Thinking the monument to sub/urban riots

Long-term research on riots

2015-2021

Ausstellung, Akademie Schloss Solitude, Januar 2016.

Ausstellung, Akademie Schloss Solitude, Januar 2016.

Ausstellung, Akademie Schloss Solitude, Januar 2016.

The long-term research in collaboration with Gal Kirn started as a residency at Academy Schloss Solitude where the first findings were presented as an exhibition and further deepened in a collective workshop.

The last fifty years of sub/urban riots in the West have seen an intensified sequence of radical disruptions, which were accompanied by a generally negative representation of rioters by media institutions and the political class. In the main, rioters have been unanimously represented as an irrational mob directed by immoral and criminal behaviour, strictly employing a form of violence bereft of any political meaning. However, when stripped of moralising and repressive discourse we find that rioters respond both to immediate police violence (brutal beatings, police killings) and to a deeper intersectional logic of gender, racial, colonial and class oppressions on the urban periphery. The sub/urban riot erupts briefly and brings deep dissent to the core of society. The instability and fleeting character of this rupture bring the permanent aspects of the everyday urban life of the poor into view: economic depravation, political exclusion, forms of racism and police violence. The central task of this exhibition has been not only to locate the generally shared characteristics of different riots, but also to intersect or connect such findings with another undercurrent in the twentieth century, namely the history of radically alternative monuments. What seems like a highly contradictory relationship at first glance- monument and riot - will be challenged by the selection of monuments presented here. The monuments on display challenge the very idea of the monument as an institution of stability and consensus, as well as the notion that the monument launches a dominant narrative and commemorative practice of the past. Rather, the monuments of this exhibition assert complex narratives and intend to achieve more than just commemoration; they challenge the very notions of permanency and consensus. In contrast with the dominant narrative of monuments, they incorporate struggle, negotiation and transformation. How can these monuments enter into productive dialogue with the riots that desire to forget the past and explode into the future? Can a monument to the sub/urban riot serve as a stable form of spatio-political intervention/negotiation, and become a permanent trigger for awareness and transformation of oppressive conditions, or should it rather attempt to resonate the solidarities of the excluded? The exhibition explores both subiects - riot and monument and works through their relationship based on the hypothesis of a dissenting monument to dissent.

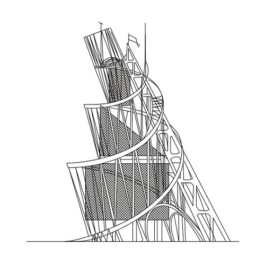

Monument to the Third International, Vladimir Tatlin, 1917

Tatlin’s monument is a dynamic structure that incorporates three revolving halls supported by a skeletal and spiral framework. It does not just symbolise the functioning of a political system, but also incorporates its functions (the central decision-making processes of the communist government and International take place in it). The monument breaks with the very idea of architecture as a static form. By contrast, the building is envisioned as a dynamic device and as an apparatus that regulates the organisational activities and conflicts of people. Tatlin’s monument is concerned with the process of becoming rather than being. As the name suggests it is a monument to the continuous becoming of the present, and is infected by a future emancipatory horizon. It represents history as a contradictory evolving process, which is never limited to national (state) issues. It is transnational, communicates and resolves; it is capable of organising and seeing things differently.

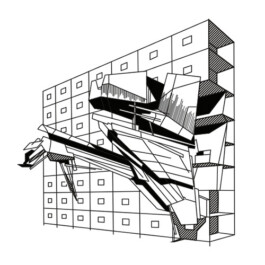

Conical Intersect, Gordon Matta-Clark, 1975

The “nonument” was articulated as a critique of urban gentrification in the form of a radical incision through two adjacent seventeenth century buildings designated for demolition right next to the Centre Georges Pompidou, which was then under construction. For the first time the monument is not a built structure, but a void, which becomes the embodied site of aesthetic and political negotiation; it is filled with meaning, criticism, questions, ideas, feelings, discourses, while the form – the spiral – shows how these continually shape, dissipate and resolve. The nonument is an instrument of social critique, a critique of the production of space in Paris. It is located at the margins of the “big stories”, which will be glorified by more permanent monuments. The nonument itself is an expression of ephemerality and thus becomes a veritable monument to the marginal, the unrecognised, and the so-called insignificant.

Yugoslav Partisan Monuments, Different authors,1960-1980

From the 1960s to 1980s in Yugoslavia a vast alternative memorial movement emerged from within the official policy of socialist modernism. Socialist modernist memorials employed peculiar aesthetic strategies that testify to the National Liberation Struggle during and after World War II. This would be initially commemorated through the common features of the massive suffering of the people and the remembrance of fascist terror and war. From the 1960s onwards, however, new modernist memorial sites encouraged gestures of resistance and emancipation that would be oriented towards the future. The monuments have in common an abstract aesthetic, manifesting a turn from the specific event to a more general notion, from the concrete political event to optimism for the present society and its future horizon. These monuments consist of large public spaces that entailed different social practices: from informing oneself, picnicking, going for a walk, to countercultural activities and acts of refusal.

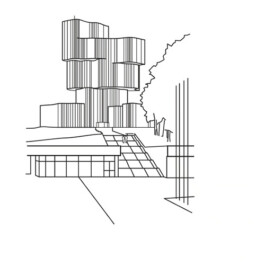

Radical Reconstruction, Sarajevo, Lebbeus Woods, 1993

Lebbeus Woods visited besieged Sarajevo during the war, where he developed a strategy that would deal with the transformation that the war caused in society. The radical reconstruction entailed a twofold hypothesis: ninety per cent of each damaged building was to be restored to its normal pre-war form and use, while ten per cent was to be built as an entirely new type of space in order to reflect the transformation society underwent during war. He called these new places “freespaces”, which had no predetermined utility, but were to engender the invention of new programmes for the use of space that corresponded to the new, post-war conditions. These “freespaces” have the potential to create a new “normal” way of being that modifies and in some ways replaces the lost one. This ten per cent, built differently from the majority, the ninety per cent, thus questions the reconstruction of an assumed normality as such. The notions of “normality” and the “everyday” as something stable and static are shaken to their foundations. Normality is something that has to be negotiated and invented constantly. The “freespaces” are thus monuments to the past, present and future transformation.

Monument to Bataille, Thomas Hirschhorn, 2002

The monument was built in an immigrant neighbourhood of Kassel during the Documenta 11, and was based on a collaborative effort of the artist and the community. It is conceived as an instrument for the inclusion of an otherwise marginalised neighbourhood and encourages an encounter between different parts of society. It first and foremost establishes connections, which were otherwise not there. As such it is divided into different elements and sites, which were defined in negotiation with and run by the community: a library for knowledge transfer and discussion, a snack bar, a TV studio, a car connecting different sites, etc. The fact that it is temporary and fragile strengthens the monument: it can be appropriated; it is not intimidating; it opens up spaces in which people can meet on the same level. It is a confrontation with reality beyond the museum space that participates in the new art trend of community monuments that are in their form open to external conflicts and discourses. The idea of how the monument is brought to the people is essential, as is the aspect that without the advice and help of the people the monument itself could not have been built.

Granby Workshop, Assemble, 2015

Following the Toxteth riots in 1981 many of the houses in Granby Four Streets were demolished. Local residents re-appropriated the remaining cluster of dilapidated Victorian terrace houses and founded a Community Land Trust. Assemble was hired and developed the refurbishment of housing, public space and the provision of new work. Granby Workshop was launched as a continuation of the process of physical transformation. It produces and sells a set of handmade items designed for the refurbished flats. Some are cast using rubble from Granby Four streets. The items are distributed to the rest of the world as small monuments of everyday life; they remind one of the capacity to transform the derelict spaces of injustice and ill-management (by the state) into something empowering. The project brings objects from one dwelling place into the dwelling place of others. You live with and from the monument, which makes it a reciprocal relationship: the transformation process forms the monument and the monument forms the transformation process. The social critique of gentrification takes place in the form of an affirmative action, revealing a concrete alternative, which makes this “ready-made” monument a part of alternative political representation.

Mahnmal gegen den Faschismus (Memorial against Fascism), Esther und Jochen Gerz, 1986

This memorial consisted of a lead-coated column, which gradually sunk under ground over a period of six years. Visitors were encouraged to inscribe their names onto the surface. The artists attempted to overcome the short-lived experience of visiting the monument by involving the visitor in a permanent co-authorship and thus a joint responsibility. In the course of the six years, however, some reactions appeared that had not been envisioned beforehand – swastikas as well as statements against immigrants. These elements gave the monument another dimension: that of an instrument that not only commemorates the past, but also makes the present reactions to the past visible. The (counter)monument problematised the traditional notion of a monument that represents the dominant history of state narrative, based on social consensus. Even though it was conceived as a monument to what in Germany is thought to be an absolute reason of state (the condemnation of its National Socialist past), it showed how the official narrative of having overcome this past is in fact a precarious and tenuous assertion. The monument here is a mirror of the manifold opinions of society. It represents the end of representation, which is completed by the disappearance of the column.

Monument to Charles Fourier, The Situationists, 1969

The statue of the utopian socialist Charles Fourier was removed by the Vichy government on the order of the Nazis occupying power. The empty plinth remained on the Place Clichy with its plaque grinded down until 10 March 1969. It was at the precise moment when a general strike was scheduled to commence, that the Situationists returned the statue of Charles Fourier to its plinth. A plaque was added on the statue’s pedestal: “A tribute to Charles Fourier, from the barricaders of the rue Gay-Lussac” alluding to the clashes of the May 1968 student protests in Paris. The Situationists used the method of “détournement” (high jacking) here for the first time in the domain of memorials. The empty plinth was like a monument in an “unfinished” state, offering a radical potential for appropriation and action. Its initial historic meaning was taken up and expanded into the reality of the then relevant political battles. Up until the municipality commissioned a new monument, the radical potential of the plinth’s emptiness and political radicality of Fourier were ever present.

Partners: Gal Kirn, Akademie Schloss Solitude, ifA Galerie Berlin, Museum of Modern Art Ljubljana